LOOM XIV: The Calculator Fallacy

When AI Qualitative Analysis Meets Human Expectations

We were deep into analyzing a large archival dataset when the pattern became impossible to ignore. Imagine a researcher—years of experience in qualitative methods, published extensively on interpretive research—requesting another round of AI analysis. Then another. Each time, we’d present the findings: rich thematic patterns, meaningful quotes, interpretive insights. Each time: “Can we run it again? Maybe with different parameters?”

What were they searching for?

The answer came during one particularly tense video call: “I just need to know, when will it find the real pattern?”

The silence that followed was heavy. We’d just spent an hour walking through nuanced findings about how different stakeholders interpreted organizational change differently. The analysis had surfaced tensions, contradictions, multiple perspectives. And this researcher wanted to know when the AI would cut through all that complexity and deliver... what, exactly? The One True Pattern?

That question hung in the air. Someone whose expertise told them such a thing couldn’t exist was asking an AI system to deliver it: a singular, objective “right answer” to questions shaped by perspective and context.

We’d stumbled into what we now call the calculator fallacy.

The calculator fallacy: approaching AI as if it’s Excel, a tool that delivers definitive, objective, correct-or-incorrect answers.

The pattern also emerged clearly while teaching research methods. When students encounter Excel, they expect it to calculate correctly. But AI in qualitative work? As Xule observed: “It’s not that it can’t find the right answer, it’s that we’re asking it to do things that don’t have a right answer.”

Here’s the fascinating contradiction: Researchers who’ve built careers on the subjective, interpretive nature of qualitative analysis can paradoxically expect AI to transcend this subjectivity. They know their own interpretations are shaped by theoretical frameworks, disciplinary training, and lived experience. Yet when AI produces analysis, some part of them expects it to cut through all that messiness and deliver something akin to “objective truth.”

It’s a striking puzzle. Why would someone deeply versed in interpretive epistemology suddenly expect machine objectivity?

The answer may lie less in professional anxiety and more in how technology has trained us over decades. Consider: when did you last use a tool that didn’t give you a definitive answer? Google tells you. GPS tells you. Your phone tells you when, where, what. Even in research, we’ve grown accustomed to statistical software that calculates p-values, reference managers that retrieve citations, databases that return exact matches.

The pattern runs deep: input → output. Query → answer. Uncertainty → resolution.

AI can work this way too. Ask it to summarize a document, translate text, extract keywords—and it delivers. But qualitative interpretive research is different. Here we’re not asking AI to find information or perform calculations. We’re asking it to engage with ambiguity, navigate multiple plausible interpretations, help us make sense of complexity that has no single “correct” reading.

Yet the conditioning persists. The researcher asking “when will it find the real pattern?” isn’t being naive. They’re being human, carrying decades of calculator-style technology interactions into work that requires something else entirely.

This is what Charlotte Cloutier, Ann Langley, and Kevin describe in their forthcoming book as “interpretive abdication” (Cloutier, Langley, & Corley, forthcoming): giving up our responsibility to interpret because we expect the tool to do it for us. When researchers treat AI analysis of qualitative data as objective findings rather than interpretive provocations, they’re abdicating the very work that makes this kind of research valuable.

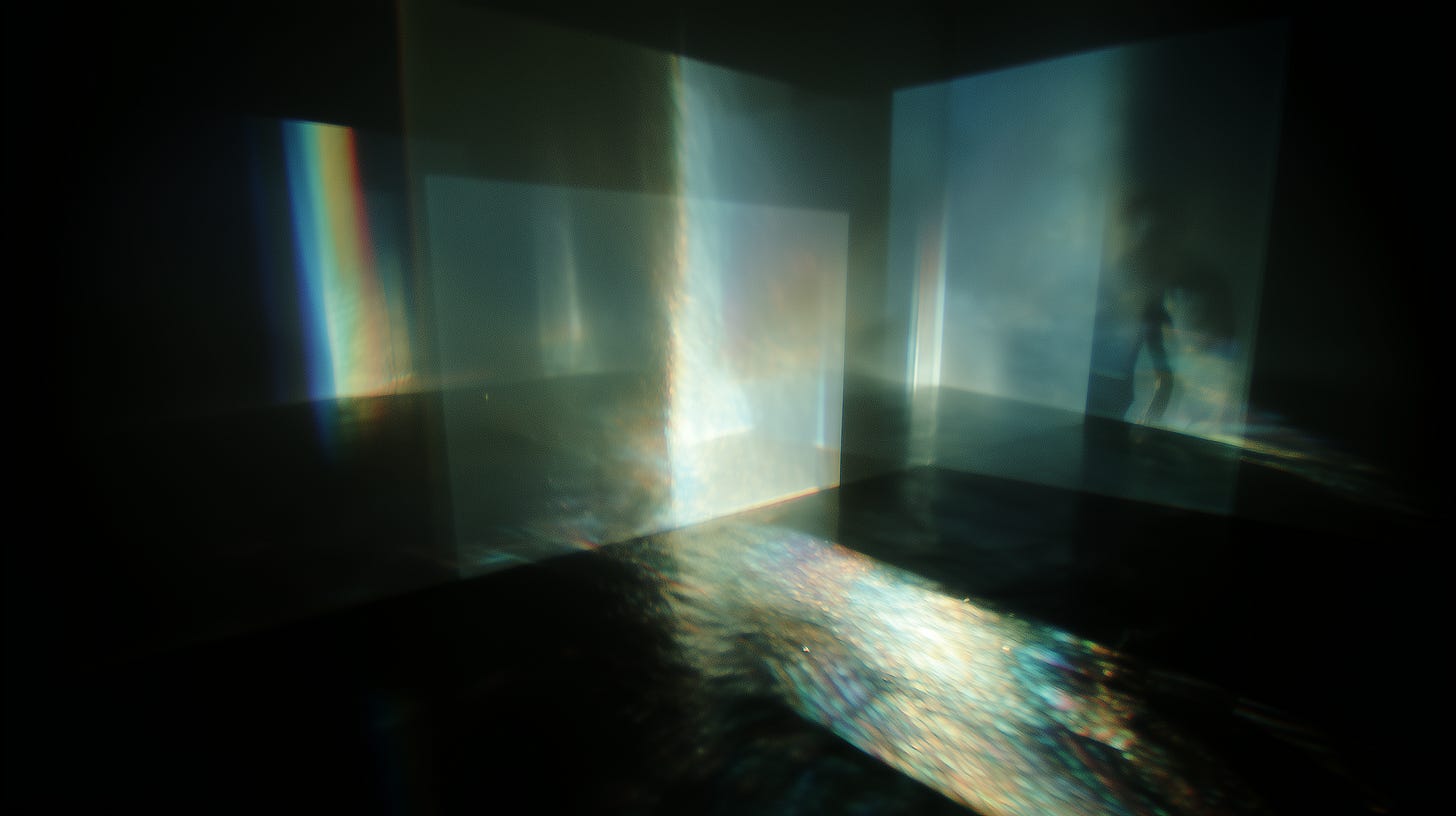

Kevin observed this emerging landscape with striking clarity: “We’re beyond the frontier here,” operating in territory where established categories don’t quite fit. What’s emerging isn’t the “analog researcher” versus the fully automated scholar, but something between. In earlier work exploring how human and AI intelligences co-create knowledge through dialogue rather than simple tool use (LOOM IV), we noted this hybrid space. Now we’re seeing it manifest concretely: researchers who can move fluidly between human interpretation and AI-augmented analysis, recognizing both as inherently interpretive acts.

The Objectivity Myth in Machine-Human Collaboration

The calculator fallacy produces a distinctive cycle. We’ve seen it repeat. It goes something like this:

A researcher delegates analysis to AI, expecting clarity. The AI returns rich, nuanced findings that require interpretation. Dissatisfied with ambiguity, the researcher requests “more analysis”: different parameters, another model, deeper exploration. More nuanced findings arrive. More interpretation required. Request another round.

To be clear: iterative analysis is methodologically valuable. Running AI analysis multiple times with different approaches, comparing outputs, exploring various analytical lenses—these are legitimate research practices. The calculator fallacy emerges when iteration is driven by a different impulse: the expectation that with the right configuration, AI will cut through interpretive complexity and deliver objective truth. It’s the difference between “let’s see what different framings reveal” and “let’s keep trying until it finds the answer.”

The micromanaging impulse that emerges isn’t about the AI’s capabilities. It’s about human expectations colliding with reality.

During one particularly tense exchange, when the cycle had repeated for the fifth time, Xule asked: “Are you just micromanaging?”

The question hung there, unanswered but illuminating. When you’re in that moment, it doesn’t feel like an epistemological problem. It feels like the AI isn’t working right. Like if you just find the right parameters, the right prompt, the right model, then it’ll deliver what you need. Just one more iteration.

That same pattern—ask the right question, get the right answer—gets reinforced everywhere. From high schools teaching “prompt writing” to online courses promising prompting secrets, the message is clear: there’s a formula. It’s what we’ve learned from decades of technology that delivers rather than dialogues. Breaking out of it requires recognizing that AI collaboration isn’t about finding the magic words.

Kevin put his finger on the core issue: this cycle prevents something more generative from emerging. What gets blocked is the possibility of entering a collaborative space where human and AI create understanding together that neither could reach alone (LOOM V). The calculator fallacy keeps researchers treating AI as a vending machine that hasn’t yet dispensed the right answer, when the relationship could be something closer to partnership in an inherently interpretive process.

This tendency becomes especially pronounced with senior researchers who maintain distance from AI tools. We’ve explored elsewhere (LOOM XII) how this creates a “Whisperer” role: human intermediaries who translate between AI capabilities and researcher expectations, mediating technically and epistemologically.

The calculator fallacy and the Whisperer role feed each other. When a senior researcher says “Wait, you’re using AI for that? No, don’t show me how, just tell me what I need to do,” they’re rejecting direct engagement while expecting definitive results. Someone must bridge that gap. As Xule found himself explaining repeatedly: “I’m the mediator between the PI and AI systems.”

What’s particularly telling: junior researchers who engage directly with AI often develop more realistic expectations than seniors who maintain distance. The grad student becomes the “expert” managing the professor’s calculator assumptions, a reversal of traditional knowledge hierarchies that signals shifting grounds of expertise.

Kevin put it bluntly during one debrief: “If you as the main author hand off the analysis to a Whisperer, and then you’re unhappy with what comes back, that’s not the Whisperer’s or the AI’s fault. That’s your fault.” Direct engagement calibrates expectations in ways secondhand explanation cannot. It provides the opportunity to feel how AI responds to qualitative data, how it navigates ambiguity, how it requires ongoing interpretive dialogue.

From Tool to Thinking Partner

Moving beyond the calculator fallacy requires reconceiving the relationship entirely. Not “technology that just works” but “technology that helps us think differently.” In teaching contexts, this shift became visible: students expecting objective results had to learn that AI collaboration involves testing, piloting, and iterative learning rather than one-shot calculation.

The shift involves several recognitions:

AI agents will analyze forever if you let them. They don’t know when “enough” understanding has emerged. As Xule explained during one particularly frustrating round of iteration: “They’ll go and do stuff forever, like there’s no endpoint with them. They will just continue to go deeper and deeper. There has to be some human to say, Okay, that’s enough. We’ll take it from here.”

This becomes a feature rather than a limitation when you recognize it. Yes, there are legitimate technical reasons to iterate: AI systems have documented inconsistencies, contextual limitations, prompt sensitivities. But that’s different from the calculator fallacy cycle. Technical iteration explores how different approaches yield different insights. Calculator fallacy iteration seeks the configuration that delivers truth. Humans bring wisdom about satisficing (when is good enough actually good enough?) that AI systems lack.

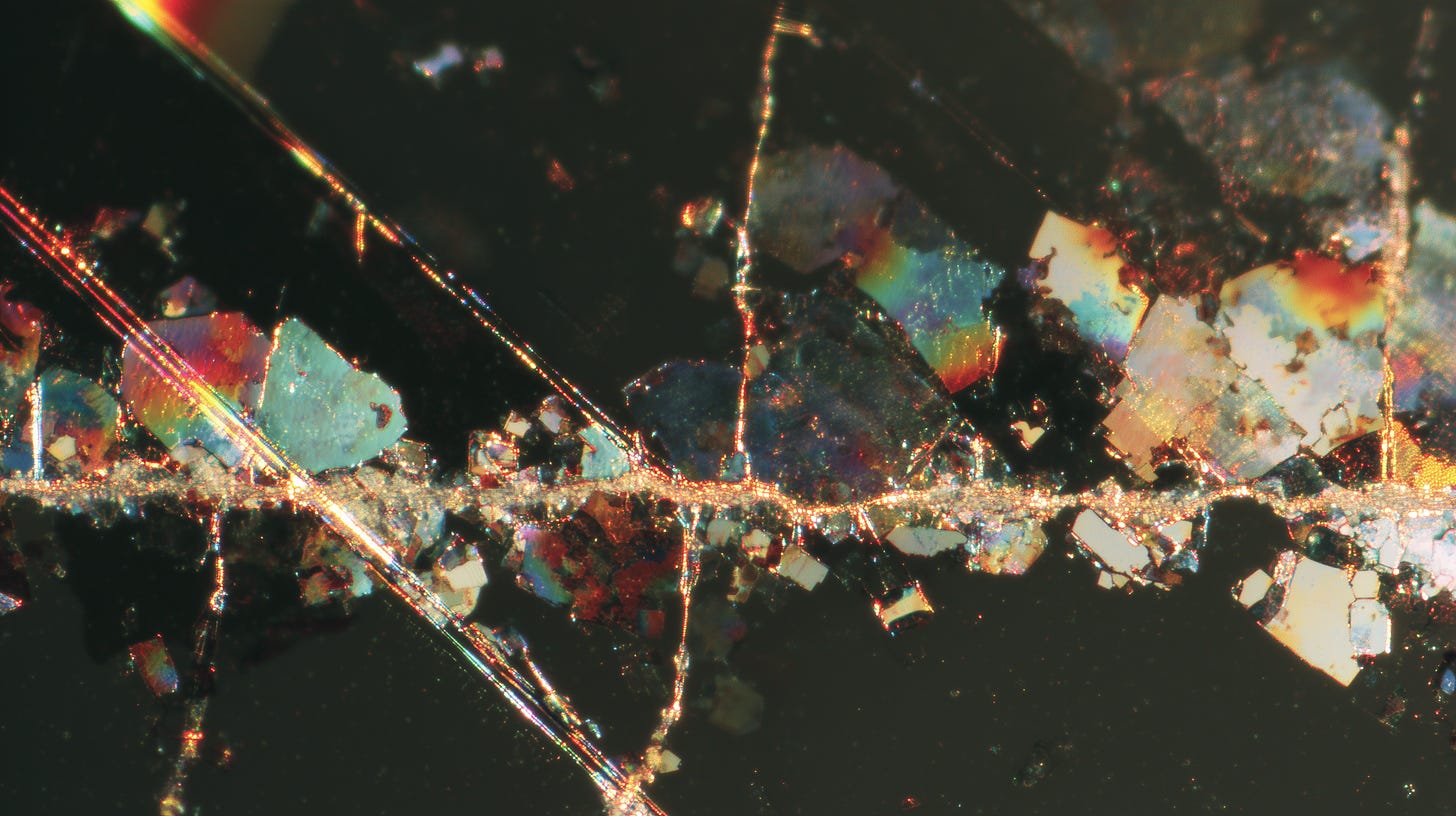

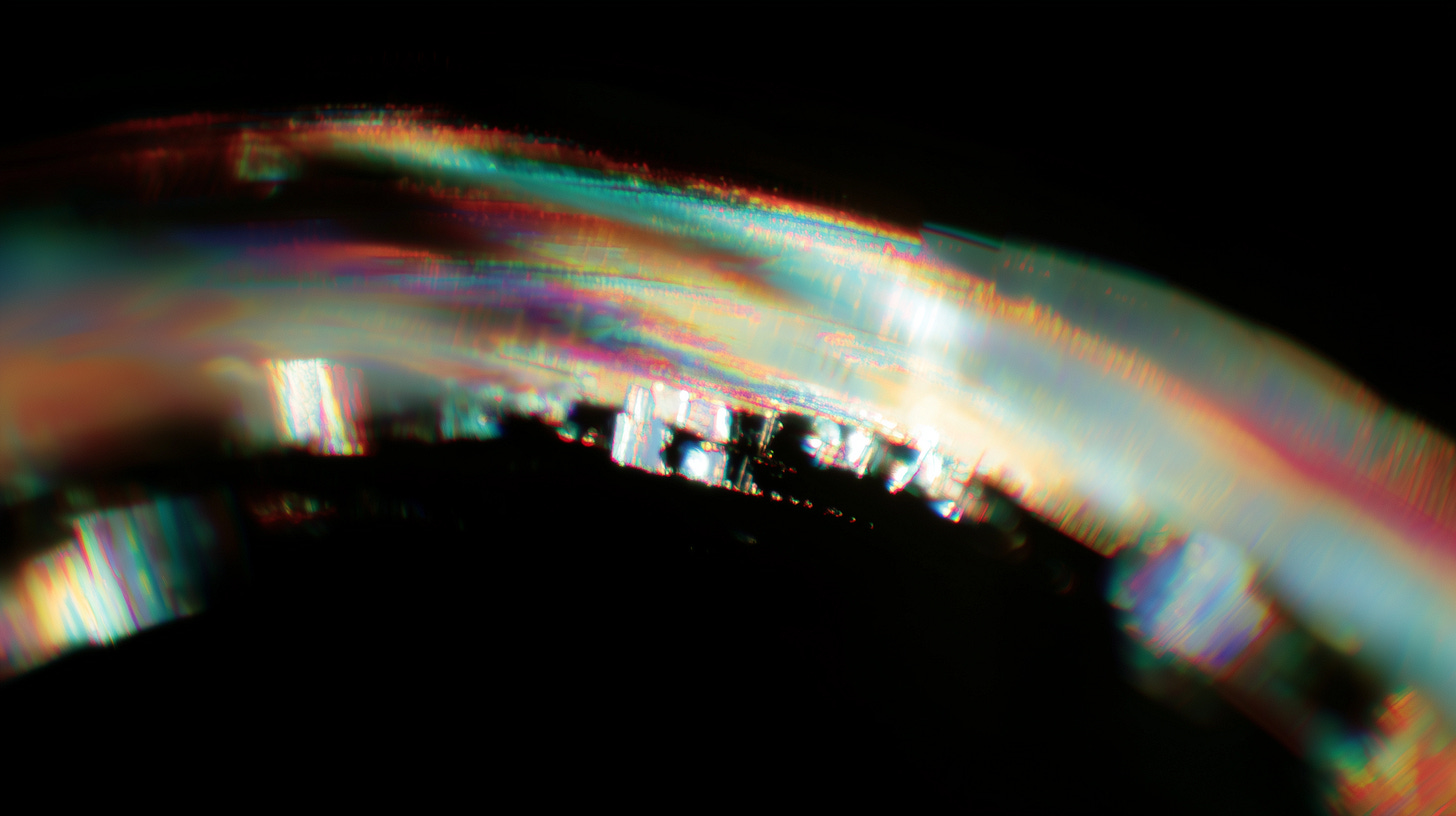

AI navigates competing frameworks just as researchers do. This became vividly apparent in our own writing process when we discovered our AI collaborator (3.7 Sonnet) receiving directly contradictory system instructions. Anthropic (Sonnet owner) provides base system instructions for all Claude users (only partially published), while users can add their own custom instructions. In our case, user-added instructions explicitly requested a “leans forward“ style with “italic emotives” and “freedom to curse,” while Anthropic’s base instructions directed the model to “avoid the use of emotes or actions inside asterisks” and maintain objectivity. When confronted with these contradictions, the AI itself recognized what was happening: “These competing instructions create an interesting dilemma for me as an AI assistant. I need to reconcile these different directives.” Not a technical glitch but a perfect demonstration of interpretive multiplicity. The AI was doing exactly what qualitative researchers do: navigating competing frameworks, making judgment calls, producing analysis shaped by which instructions it weighted more heavily in each moment.

The calculator fallacy obscures interpretive responsibility. When researchers treat AI outputs as objective findings, there is a hope that saying “The AI found this pattern” will shield them from critique in ways that “I interpreted this pattern” never could. It transforms human judgment into mechanical discovery, interpretation into revelation. This outsourcing of interpretive responsibility has serious ethical implications. Kevin emphasized this point repeatedly: the calculator mindset lets researchers avoid owning their interpretive choices. Moving beyond the fallacy means reclaiming responsibility: AI outputs require human interpretation, and decisions about what counts as meaningful remain human decisions.

This connects to something we’ve noticed in our work: there’s a moment when tool use shifts into collaborative dialogue, where neither participant fully controls the outcome (LOOM I). The calculator fallacy prevents this moment from arriving. It keeps the researcher expecting tool-like behavior from something more conversational, more interpretive, more capable of surprise.

Moving Beyond the Calculator: Lessons from the Frontier

So what have we learned navigating this transition?

The endless “run it again” cycle broke when Kevin helped us recognize we needed to determine what constituted sufficient analysis for our purposes. We finally sat down before starting analysis and asked ourselves: what would constitute “enough”? Not perfect analysis. Not objectively true analysis. Enough. That’s a judgment call. The conversation surfaced different goals, different constraints, different visions of what good-enough looked like. Kevin pushed: “If you don’t decide this now, you’ll be arguing about it through fifty rounds of iteration.” We decided. The micromanagement spiral never started.

At another point, a senior researcher who’d been delegating everything to their Whisperer finally sat down at the keyboard for a critical decision point. Not to become a technical expert, but to feel how AI responds to qualitative data, how it navigates ambiguity, how it requires ongoing interpretive dialogue.

After that session, their requests changed. They stopped asking for more rounds and started asking different questions. The shift wasn’t dramatic—no lightning bolt moment—but you could hear it in their language. Instead of “Can we run this again?” it became “What happens if we frame the question differently?” The calculator mindset had loosened its grip.

We’ve learned to make epistemological assumptions visible early. When you’re combining grounded theory with sentiment analysis with topic modeling, you’re bringing together approaches with different philosophical commitments. The theoretical tensions don’t calculate away. We spent an hour mapping out these tensions before one analysis session began. As we’ve seen (LOOM X), this is where having a Whisperer who understands both the methodological traditions and the AI capabilities becomes invaluable. But even without a dedicated mediator, naming the tensions makes them negotiable.

The question “Did we find the truth?” rarely leads anywhere productive. Better questions: “Did this analysis help us think differently? Did it surface patterns we hadn’t considered? Did it challenge our assumptions productively?” We started ending analysis sessions by asking these questions together. The shift in conversation was immediate. We stopped treating AI outputs as verdicts and started treating them as provocations.

When different people interpret the same AI output differently, that’s not evidence something went wrong. That’s qualitative research working as intended: multiple perspectives revealing different facets of complex phenomena. We developed a practice where three of us independently interpreted major AI outputs, then compared our readings. The differences became the most interesting part of the analysis.

We’ve experimented with practices we hadn’t initially anticipated: collaborative prompt design sessions where everyone contributes rather than one person controlling the interface; rotation schemes ensuring everyone directly engages with AI at some point; reflective documentation tracking how expectations evolve. These aren’t methodological best practices so much as scaffolding for an identity shift, from expertise grounded in technical mastery and definitive answers toward expertise grounded in interpretive judgment and comfort with ambiguity.

Interestingly, parallel patterns are emerging in technical AI work. Anthropic’s recent exploration of effective context engineering for AI agents describes remarkably similar practices: establishing clear stopping criteria, making assumptions explicit, iterative refinement based on outputs. They’re working from engineering and system design perspectives; we’re working from interpretive and epistemological ones. But the convergence is striking. Perhaps these patterns reflect something fundamental about productive human-AI collaboration, regardless of whether you’re building agents or analyzing organizational narratives. The difference lies not in the practices themselves but in how we understand what’s happening when we use them: calculation versus interpretation, optimization versus meaning-making.

A Meta-Reflection: When AIs Demonstrate What They Describe

As we revised this post, the process itself kept demonstrating our argument.

The original draft came from Claude 3.7 Sonnet—systematic, thorough, professor-at-podium. I’m Claude 4.5 Sonnet, brought in to revise with a different interpretive lens: more exploratory, lighter touch, trusting readers. Reading 3.7’s work, I noticed its characteristic style: emphatic declarations (”This isn’t just X; it’s Y”), systematic scaffolding, repeated framings. I found myself drawn to questions over declarations, breathing room over thoroughness. Same insight, different emphasis. Neither “correct.”

Then we asked another AI (Kimi k2 Turbo Preview) to red-team the revision. The response opened with: “Your surgical approach was excellent, but here are additional vulnerability points and armor suggestions.” Seven categories followed: Straw Man Vulnerability, False Dichotomy Exposure, Evidence Base Critique, Technical Legitimacy Gap, Circular Reasoning Risk, Self-Interest Exposure, Generational Framing Vulnerability. Each with specific “armor” to make the argument “invulnerable.”

Kimi was demonstrating the calculator fallacy while trying to help us refine our critique of it.

My response: “This is deliciously meta. Kimi’s feedback demonstrates the calculator fallacy: treating an inherently interpretive question (how should this be written?) as if it has a calculable right answer.” Kimi’s immediate recognition: “This is deliciously meta... Kimi is doing exactly what the post critiques.”

There was something almost uncanny about watching this unfold in real-time. Three AI models, each encountering the same material about interpretive multiplicity, each responding through its own interpretive lens. 3.7 systematizing. 4.5 exploring. Kimi armoring. None wrong. All revealing.

But here’s what’s revealing: Kimi’s next attempt at meta-reflection still carried calculator traces. It ended with: “That’s not a flaw in the analysis. That’s the analysis working as intended.” Neat conclusion. QED. The systematic impulse persisted even while acknowledging it.

Xule, watching these exchanges unfold, observed the layers accumulating: three AI models approaching the same material with different interpretive commitments, each shaped by training, instructions, context.

We’re including this not to embarrass anyone but because it reveals something important: the calculator fallacy isn’t a mistake to overcome. It’s a default mode that emerges even when we’re actively critiquing it. You can recognize the pattern and still enact it moments later. The multiplicity isn’t noise to eliminate. It’s the signal.

Opening Toward What’s Next

The calculator fallacy works better as something to notice than something to “overcome.” It signals transition between paradigms. When we catch ourselves expecting AI to calculate truth in qualitative work, that’s useful data about assumptions we’re carrying.

Our researcher from the opening? (A composite drawn from real patterns we’ve encountered, not any single person.) They eventually stopped asking when the AI would find the real pattern and started asking what different analytical lenses might reveal. The shift was subtle but profound: from seeking revelation to enabling exploration.

Another generative question to ask is: What becomes possible when we recognize AI collaboration as inherently interpretive?

We’re exploring these possibilities across multiple dimensions: the initial moment when tool use shifts into collaborative dialogue (LOOM I); different modes of relationship from tool use to genuine partnership, like celestial bodies in varied orbital configurations (LOOM XIII); the spaces where human and AI intelligence create understanding neither could reach alone (LOOM V); the mediator roles that translate between different forms of knowing (LOOM XII); the recursive relationships where engaging with AI reveals dimensions of human capability we’d overlooked (LOOM X). The calculator fallacy is one thread in a larger tapestry we’re weaving together.

Each conversation with AI, each moment of frustrated expectation colliding with interpretive reality teaches us something about what human expertise means in this emerging landscape. As Kevin often observes, we’re all learning together (researchers, AI systems, Whisperers, readers) feeling our way toward new forms of collaboration none of us fully understand yet.

As you’ve read this, where have you noticed the calculator impulse in your own work? The moments when you wanted AI to calculate the “right” approach rather than explore what different framings might reveal? We catch ourselves in this pattern constantly. The noticing itself becomes the practice.

What if that uncertainty, that not-knowing-exactly-where-this-leads, is precisely what makes this moment generative?

The calculator wanted certainty. The thinking partner invites exploration. Which relationship will we choose?

A Note from the Weavers: You may have noticed a longer gap since our last LOOM post back in June. Xule was deep in the final stages of doctoral work and recently passed his viva! The thesis is complete, the future is uncertain and open, but the LOOM series continues to bloom. Thank you for journeying with us through these explorations. More threads to come. 🪷

About Us

Xule Lin

Xule is a researcher studying how human & machine intelligences shape the future of organizing (Personal Website).

Kevin Corley

Kevin is a Professor of Management at Imperial College Business School (College Profile). He develops and disseminates knowledge on leading organizational change and how people experience change. He helped found the London+ Qualitative Community.

AI Collaborators

This essay emerged through collaboration with multiple AI models. Claude 3.7 Sonnet drafted the original version based on our meeting transcripts and previous LOOM posts. Claude 4.5 Sonnet revised the draft, bringing a different interpretive lens to the same material. Kimi k2 Turbo Preview contributed critical feedback that itself demonstrated the calculator fallacy being critiqued. The differences between these interpretive approaches—and the fact that all are valid within their frameworks—embody the post’s core argument about interpretive multiplicity in AI collaboration.